Alyssa McLemore’s grandmother called to tell her to come home early on a Thursday evening in April 2009. The 21-year-old’s mother had a serious autoimmune disease and was not doing well.

McLemore, a member of the Aleut tribe, was only about six miles from the home she shared with her three-year-old daughter, mother and other family in Kent, Washington, a sprawling city just south of Seattle. She agreed to get on a bus and head back.

When over an hour went by and McLemore still hadn’t shown up, her family had started to worry. The young woman with a cheery personality and a penchant for dancing was close with her mother and young daughter, and devoted much of her time to taking care of them, according to her aunt, Tina Russell. It wasn’t like her to not come home, she told the Guardian.

A few hours later the family received a knock on their door from two Kent police officers. They said McLemore had called 911 asking for help, and they had come to see if she was home.

“At that point, we were trying to tell the police we don’t know where Alyssa is, she’s been gone,” said Russell. “We got the standard, ‘You have to wait to report her missing, she’s grown, she can leave when she’d like. She hasn’t committed any crimes.’”

Four days went by before the missing persons report was filed and the investigation into McLemore’s disappearance was officially opened. Ten years later, her family is still looking for answers.

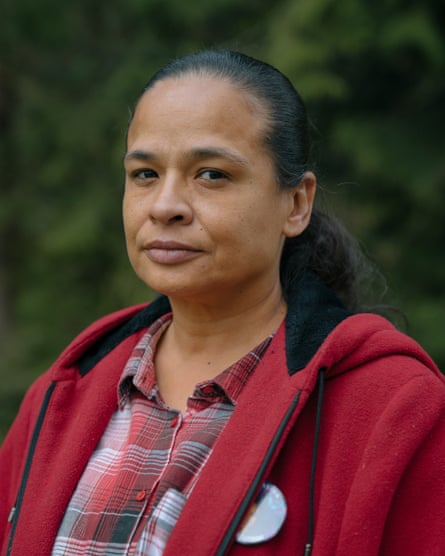

“Every time a body’s found, our whole life comes to a halt,” said Russell.

McLemore is one of thousands of Native American women and girls who have disappeared in the US, but her case is almost impossible to put into context, because there is no single federal database tracking how many people like her go missing every year.

According to FBI figures, Native Americans disappear at twice the per capita rate of white Americans, despite comprising a far smaller population. Research funded by the Department of Justice in 2008 found Native women living on tribal lands are murdered at an alarming rate – more than 10 times the national average in some places.

But with nearly three-quarters of American Indian and Alaska Natives living in urban areas, those crimes are not confined to reservations or rural communities.

In a recent report from the Urban Indian Health Institute (UIHI) researchers said they contacted police departments in 71 cities, but more than 60% would not demonstrate that they were accurately tracking disappearances, or provided them with compromised data.

The UIHI report identified Seattle as the city with the highest number of cases. Annita Lucchesi, a Southern Cheyenne descendant and cartographer who co-authored the report, said that although Seattle is seen as a liberal space, it’s not that way for everyone.

“Depending on who you are, you have a drastically different experience of the city,” said Lucchesi, who has spent the past four years building a database of missing and murdered indigenous women and girls. “So if you’re a Native woman you’re at risk for all this violence and probably have experienced some form of violence that the rest of the city is completely unaware of.”

Of 506 cases of missing and murdered Native women the UIHI report identified as having taken place in those 71 cities – a total it admits is a vast underestimate – some were tied to domestic violence, sexual assault, police brutality or a lack of safety for sex workers, but the overall reasons for this epidemic are much broader. At its core, campaigners say, is institutional and structural racism, gaps in law enforcement response and prosecution, along with a lack of data.

“I wouldn’t say that we’re more vulnerable, I’d say that we’re targeted,” said Lucchesi. “It’s not about us being vulnerable victims, it’s about the system being designed to target and marginalize our women.”

In the days and weeks after McLemore disappeared, Russell remembers police collecting a pair of her long, white go-go boots to take a DNA sample, and interviewing the family about everything from who her friends were to whether she did drugs.

But it would be two years before the family’s DNA was collected and submitted to the National Missing and Unidentified Persons System, a clearing house for missing, unidentified and unclaimed person cases in the US, according to Detective Brendan Wales of Kent police, who has been on the case for eight years. Washington state law requires this be done after 30 days or whenever criminal activity is suspected.

Probably because of McLemore’s appearance, her ethnicity was recorded as Asian, not Native American, in her police file – a mistake that would take about seven years to correct.

Racial misclassification is one common problem in police investigations, and contributes to the lack of accurate and consistent data collection on cases such as McLemore’s.

In fact, possibly due to her racial misclassification, McLemore’s disappearance was not included in the UIHI report.

Wales said in the decade since McLemore’s disappearance Kent law enforcement officials have documented instances where they worked on the investigation 48 times. He praised the investigators, saying: “The detectives who were originally on the case, well, in short they worked their butts off following down this, that.”

Earth-Feather Sovereign, co-founder of the not-for-profit advocacy group Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women Washington (MMIWW), also has firsthand experience of investigations into the disappearances and deaths of Native women.

Her close friend Lisa Jackson was 28 years old when she was killed in Seattle in the summer of 2017. A couple had been temporarily staying with Jackson and her boyfriend. According to Sovereign, when Jackson told them they needed to move out, Jackson and the woman got into a fight, which resulted in Jackson being shot and killed.

When the family asked local detectives to further investigate her death, she said they were told there wasn’t enough funding to do so.

“I just feel like that they just wanted to close up the case quickly and get it over with,” said Sovereign. “I feel like they thought that she really didn’t matter.”

Lawmakers and law enforcement officials in Washington state are trying to tackle this issue. A bill signed last week by Jay Inslee, the Democratic governor and 2020 presidential candidate, will create two liaison positions within the Washington state patrol, the state’s police agency, whose job will be to build a relationship between governmental agencies and Native communities. It also requires the state patrol to develop a protocol for law enforcement’s response to missing indigenous persons.

Last year, lawmakers approved legislation requiring the Washington state patrol to meet with tribes and law enforcement agents, and produce a study by June 2019 detailing the number of missing Native American women and offering recommendations on how to address this problem.

Captain Monica Alexander, of the Washington state patrol, has helped to lead this work and repeatedly traveled to meet with tribes across Washington. Sometimes hundreds of people have attended these meetings. Alexander said many people talked about their experience of being told by police that they had to wait 72 hours to report a missing person, something that is not a set requirement.

But she’s had little luck collecting information from tribes on how many people are missing or murdered, along with the location of each crime.

“We learned while we were out on tour that there’s a lot of people that just absolutely don’t trust law enforcement in general,” she said. “We really have to let them know, ‘listen, we truly have your best interest at heart. We want to help eliminate this problem.’”

But after so many reports of mishandled or even possibly ignored cases, building that trust will take time.

At the national level, a bipartisan team of senators recently reintroduced “Savanna’s Act”, a bill dedicated to Savanna LaFontaine-Greywind, a Native American woman who was killed in 2017 in North Dakota. The proposal would require the Department of Justice to develop guidelines for how to respond to cases of missing and murdered Native Americans and report data on these crimes.

On a Sunday in early April, McLemore’s father, grandmother, aunts, cousins and dozens of other family and friends gathered at a large park in Kent to mark the 10th anniversary of her disappearance. The space was filled with red heart balloons, photos of McLemore and other missing indigenous women, along with signs that said, “We need closure. The pain is torture.”

The group spent the afternoon talking about their memories of McLemore and anguish at not knowing what happened to her.

“We just want comfort, we just want to know, so that every McLemore and every person that loves Alyssa, everybody that knew her, every family member will be able to get a good night’s rest for once in 10 years the moment that she comes home,” Shawni Jackson, McLemore’s cousin from Kent, said to the group.

There were plenty of tears, but also hugs, smiles and a lot of barbecue. After a few hours, Russell, McLemore’s aunt, invited everyone to write a short note to McLemore and other loved ones on balloons. With arms wrapped around one another, the group gathered in a large circle surrounding McLemore’s family. They then released their messages as two eagles flew overhead and a quartet of women drummed and sang:

“Sister, sister, I want you to know.

You’re so strong and beautiful.

I gotta know, where did you go.

I think of you every day.

Since you’ve gone away.”