This weekend, hundreds of thousands of people will gather to mark the completion of the transcontinental railroad in Utah 150 years ago.

On May 10, 1869, the Union Pacific Railroad from the East and the Central Pacific Railroad from the West joined together with a spike on a summit north of the Great Salt Lake. With each blow, a letter was tapped into the first transcontinental telegraph. D-O-N-E. Done. And celebrations erupted on both coasts, as well as on Promontory Summit.

Some will commemorate the unifying vision of the railroad and what it did to connect East and West in the years after the Civil War.

Others are still struggling to bring their part of that history to the forefront.

Chinese Laborers | The Native Americans | The Intersection of Religion and Social Change

CHINESE LABORERS

Tens of thousands of Chinese laborers are believed to have worked for the Central Pacific Railroad in the creation of the transcontinental railroad. They came to the United States from parts of China experiencing war and poverty and did the jobs that few wanted to do, according to the Chinese Railroad Workers in North America Project.

Taylorsville Justice Court Judge Michael Kwan is a descendant of a Chinese railroad worker. Because the railroad companies often did not include the names of Chinese workers in their payroll records, Kwan’s family doesn’t know the name of his maternal great-great-grandfather. But stories about him have made it to the present.

“It’s a story that’s passed down to teach each succeeding generation that they should be thinking about future generations,” Kwan said.

The Chinese worked alongside Irish and Greek immigrants, freed slaves and former Civil War soldiers.

It was hard work, and especially dangerous for the Chinese and other laborers for the Central Pacific Railroad who worked through some of the toughest terrain and harshest weather, Kwan said. Not only did the workers have to endure bone-chillingly cold winters, they also had to drill — by hand — through the solid granite in the Sierra Nevada mountains.

Even so, the Chinese laborers’ hard work didn’t earn them much respect from their employers. They were beaten, paid less and had to pay for their own food, unlike white workers.

“They were thought of as just another tool,” Kwan said. “So (their employers) didn’t record the names of those who died. They didn’t bother to collect bodies or search for them. They were found when spring thaw came.”

In 1919, during the 50th anniversary of the completion of the railroad, a parade in Ogden featured three former Chinese workers: Ging Cul, Wong Fook and Lee Cho.

“These Chinese railroad workers were actually three of the eight Chinese railroad workers who laid a ceremonious last tie in the 1869 celebration,” said Max Chang, a board member of the Spike 150 Commission coordinating this year’s celebration. “The Tribune wrote they finally had their day of glory.”

Fifty years later, in 1969 at the 100th anniversary, Philip Choy, the then-president of the Chinese Historical Society of America, expected to get time to recognize Chinese laborers and present a commemorative plaque. But their time was inexplicably cut from the schedule. Some people believe the agenda became too tight because of the appearance of western movie actor John Wayne at the event, Chang said.

“To add what I call the great Salt Lake salt to the wound, John Volpy, the Secretary of Transportation at the time, then gave a speech which basically said, ‘Who but Americans could lay 10 miles of track in one day? Who but Americans could dig tunnels through the solid granite of the Sierras?”

That speech offended Choy and others in the Chinese community,

“You didn’t see Charles Crocker, Leland Stanford, or Mark Hopkins down in the railroad hammering away, setting black powder,” Michael Kwan said, referring to prominent Central Pacific Railroad tycoons. “It was the Chinese laborers and they were ignored.”

This year, the Spike 150 Commission is hoping the 150th celebration will be the most inclusive one yet, Chang said.

Michael Kwan’s sister is state Rep. Karen Kwan, D-Murray, and she has been pushing for recognition of Chinese workers as well. She proposed a bill this legislative session — now law — looking to recognize railroad workers like her ancestor.

“Because of the sacrifices that these men did we continue to have a proud heritage and tradition of railroads,” Kwan said in a March 1 House Transportation Committee hearing.

The new law means May 10 is not just about celebrating trains. It’s also Railroad Workers Day in Utah — thanking workers of the past and present.

NATIVE AMERICANS

On a recent clear spring day, Darren Parry stands next to his truck in front of the Golden Spike National Historic Park. The landscape hasn’t changed much in 150 years. Parry looks southeast, gesturing toward a nearby bluff.

“The Shoshones would sit up there and watch as the workers from the east and from the west made their way towards this point,” Parry, the chairman of the Northwestern Band of the Shoshone Nation, said.“My grandmother said they were always fascinated with the Chinese [rail workers]. The Chinese reminded them of little ants scurrying here and there, and their work ethic was really impressive to the Shoshone people.”

But, the railroad would come to symbolize a deep, painful loss for many Native American tribes displaced by western expansion.

“The native people who live closest to the line of the railroad are going to experience its impacts in the most intensive ways. But that is not necessarily a new thing,” said Greg Smoak, director of the American West Center at the University of Utah.

After the Civil War ended in 1865, the federal government turned toward what is called the ‘Indian Problem,’ Smoak said. While the government had been pushing tribes onto reservations for decades as a way to control them, the railroad intensified that effort.

By the time the trains arrived, “Shoshonean people from central Nevada all the way across southern Wyoming had already experienced an invasion of overland immigrants,” Smoak said.

The historian calls the railroad an “intensification” of westward expansion. It also played a role in massive bison hunts of the late 1800s, when demand for hide drove the animal to the brink of extinction. The railroad helped carry thousands of hides back east where they could be processed into fine leather.

That major depletion of bison herds “was the death knell to Native American cultures across this country,” Shoshone leader Darren Perry said.

The Shoshone leader is the only tribal representative on the Spike 150 Commission, the group that’s planned this year’s 150th anniversary event at Promontory Summit.

“As we party and celebrate one of the greatest achievements in the history of this country — I believe — I think it’s just important that we take a second to acknowledge what it did to Native American communities going forward,” he said.

This year, Parry wanted to bring Native American perspectives to the forefront. But his efforts haven’t been embraced by all.

He reached out to about a half-dozen tribes including the Northern Arapaho, Cheyenne, Sioux and others, asking if they would share stories or oral histories about the railroad. Parry wanted to include them in talks and presentations he has been giving around the state leading up to this weekend’s events.

In some cases, the tribal members promised to speak with elders. But in the end, he never heard back from any of them.

KUER reached out to some tribes, but did not receive a response.

Parry said he understands why some tribes are still unwilling to share their points of view about the railroad, and that their silence on the matter speaks volumes.

“You don’t really want to remember and pass down painful, painful memories,” he said. “The railroad, to those other tribes that were directly affected, was a very painful reminder of what had happened to their people.”

THE INTERSECTION OF RELIGION AND SOCIAL CHANGE

Jeffrey Mahas carefully places two family photos of his ancestors into a scanner on the third floor of the LDS Family History Library in downtown Salt Lake City.

As a scanner whirs and hums, digitizing the sepia-toned images of his relatives, it’s hard not to notice that Mahas, a bespectacled and mustachioed man with a bowtie, looks as though he might have stepped right out of the images.

“The ones I’m here to talk about today are John and Agnes Humphrey. They came on the railroad in 1871,” said Mahas.

John and Agnes are Mahas’ great-great-great-grandparents. He is a church historian who also uses his sleuthing skills to uncover his own family history.

They traveled by train from the South where after the Civil War they’d converted to Mormonism and set out for Utah Territory in search of Zion. John and Agnes’ oldest son came first, then the rest of the family followed.

For 19th Century Mormon pioneers, the railroad was an answer to prayer, reducing an arduous several-month journey to a comfortable week-long trip.

The new mode of cross-country travel was especially important for John, a disabled Civil War veteran, and Agnes, who was sick with tuberculosis. Without the train, they likely wouldn’t have made the journey.

For members of the LDS Church, genealogy is deeply personal. They believe they’ll be reunited with their ancestors in the afterlife and baptize those who were not of the faith.

In one photo, sober-faced John and Agnes sit posed side-by-side in their Sunday best looking directly at the camera along with an adolescent son, standing in between them.

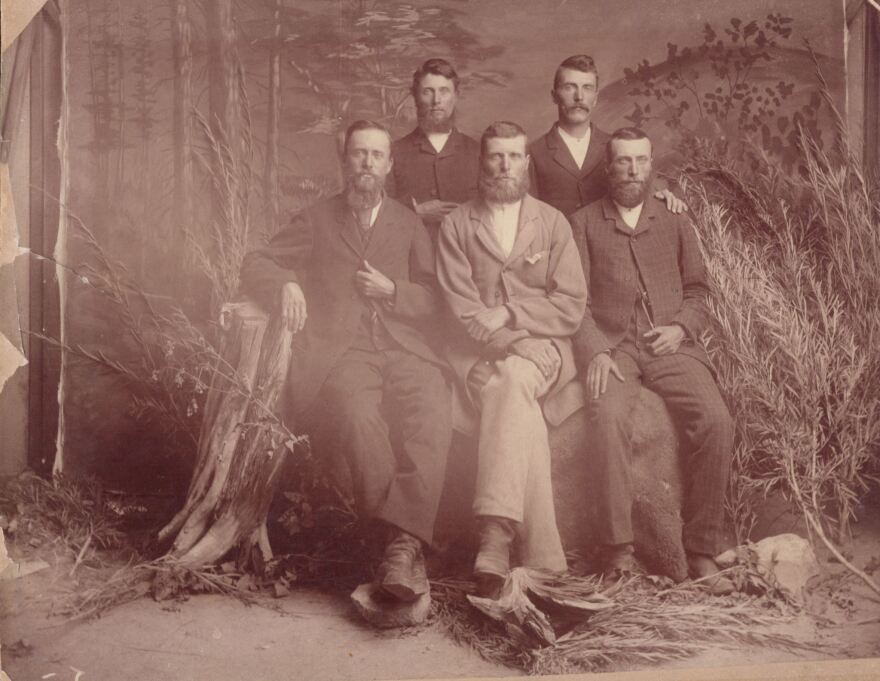

In the other picture, five burly, full grown men — more of John and Agnes’ sons, pose sitting and standing against a backdrop of the old West, sporting beards and mustaches and suit jackets. Their dusty boots give away the harsh conditions in their new home.

But that also worried some, said Brent Rogers who is also an LDS church historian.

“George Q. Cannon, who was an apostle for the church said, quote, ‘We are told openly and without disguise that when the railroad is completed there will be such a flood of civilization brought in here that every vestige of us, our church and institutions shall be completely obliterated,’” Rogers explained.

Standing inside the South Visitors’ Center at Temple Square he points to a replica of a wagon used to haul rock to build the massive place of worship.

“The granite looks to be about maybe 3- or 4- feet wide by 2- feet tall,” said Rogers.

Settlers quickly realized that trains could help them quite literally build the church. Before the train those huge slabs of rock took days to move 20 miles to the temple, said Paul Reeve a professor of Mormon studies at the University of Utah.

“They were taking very large and heavy stone out of Little Cottonwood Canyon and dragging it into Salt Lake on carts pulled by oxen,” he said. “And sometimes it would take two or three days to pull a single block of stone from Little Cottonwood Canyon into downtown Salt Lake City.”

When Brigham Young arrived in the Salt Lake Valley in 1847, he wanted to cut ties with the outside world. The Christian sect had been chased out of the Eastern United States and sought isolation. At first, Young worried the train would make mormons dependent on outsiders, Reeve said.

“Will this religious flock that he is trying to cultivate, become enamoured with the material wealth of the outside world, the fashions of the East?” he said. “Will they become dependent upon outside material goods rather than their focus be on the Kingdom of God?"

But in the early 1850s, Young began to see the benefits of the railroad. He convinced his followers that it was the only way to expand the reach of the church. He became one of the railroad industry’s first investors.

Young told his followers: “Mormonism must indeed be a poor religion if it cannot withstand one railroad.”

The railroad also transported social change, especially for women’s rights. The news used to come by stagecoach and the train sped up the delivery of newspapers and magazines, said Katherine Kitterman of Better Days 2020, a nonprofit that highlights Utah women’s history.

Increased access to news and information via train delivery put Utah women in touch with women in other states working for equality and suffrage, such as Susan B. Anthony and her newspaper, The Revolution.

Kitterman highlighted Sarah Kimball, a well-known Mormon leader in Salt Lake City, and women’s suffragist, who received copies of Anthony’s paper.

“She was able to get those papers much more quickly, read about them and then incorporate some of those strategies into her own work for women,” Kitterman said.

After Utah became the first state in the country where to allow women cast a ballot in 1870, Anthony and another national suffragist Elizabeth Cady Stanton visited by train in 1871.

The suffragists gathered in the Salt Lake City tabernacle and spoke with local women about their voting rights, Kitterman said.

“They had heard about these women who were the first to actually cast ballots and they wanted to see for themselves what was actually going on,” Kitterman said the leader of the LDS Church had been right to worry that the train would bring new, radical ideas to the region.