Mapping project gives state insight into oysters, future restoration sites

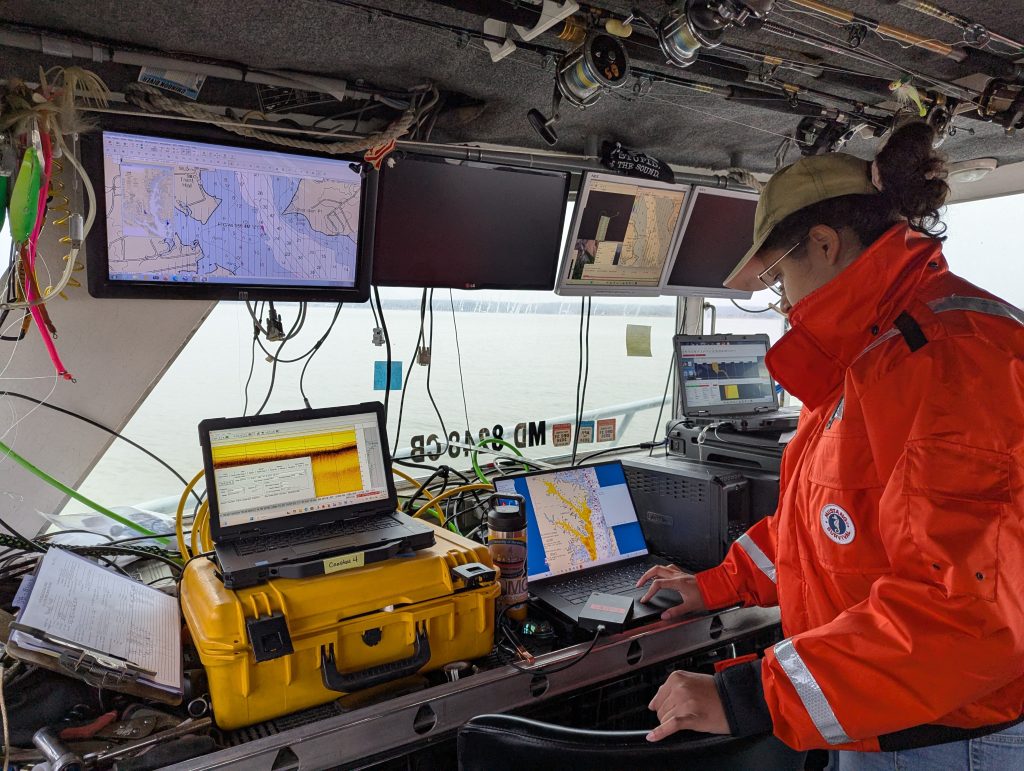

Gillian Branam, a geologist with the Maryland Geological Survey, analyzes data on board the Bay bottom mapping boat. Photo by Joe Zimmermann, Maryland DNR

Not long after the sun came up, a team of Maryland geologists set out on the Patuxent River.

As they approached the Upper Patuxent Sanctuary, the team prepared the sensing equipment and took preliminary measurements in the water. With a custom crank-and-pulley system, they lowered the interferometric side-scan sonar off the bow. Soon after, they deployed a magnetometer and a sub-bottom profiler to trail in the wake of the boat.

Then they headed forward, following a long, straight line. It was the first line of the day, but one of hundreds the team has conducted over the last two years, part of the diligent work of mapping much of the bottom of the Chesapeake Bay and its tributaries.

Though the Maryland Geological Survey has collected data on the sediment and underlying structure below the water of the Bay for decades, its current work focuses on areas that serve as possible oyster habitat.

“We need this data to determine where the suitable bottom is,” Stephen Van Ryswick, the Director of the Maryland Geological Survey, said from the survey boat. “We look at where the new data gives us the most value, where new data can help us make decisions.”

It takes careful and precise work to arrive at that data. To make a map of the bottom of a section of the Bay, the team follows a routine they liken to “mowing the lawn”—going back and forth in close, slightly overlapping lines to allow their sensing equipment to get complete coverage. The captain of the boat executes tight turns to keep them on track.

Joseph Allman, MGS geologist, prepares the torpedo-shaped magnetometer, which detects metal material, including potential shipwrecks or archeological artifacts. Photo by Joe Zimmermann/DNR

Before setting out the equipment, the team took a measurement of the velocity of sound across different depths of the water, letting them make corrections for subtle changes. As they coursed along a steady line, the sensing equipment beamed live data onto the boat. The quantities of data are considerable, often up to 30 gigabytes in a day. While the staff processes much of the data back in the office, some of the information from the riverbed goes directly to the screens on the boat.

Survey geologists Joseph Allman and Gillian Branam watched closely as monitors displayed the trajectory of the boat and the readings from the equipment. A red column marked the bathymetry, the depth of the water below, while yellow bars pocked with red dots showed the “loudness” of the riverbed, where the sonar finds harder surface layers. Sometimes the readings illuminate paleochannels, ancient river channels from 18,000 to 450,000 years ago, now filled in with sediment.

“A lot of the day is paying attention to five different screens, and each one has at least five different things going on,” Branam said.

They collect data in the winter months—usually from November to March—so that crab pot floats and other boats won’t disrupt their fine tracings of waterways, and so schools of fish and submerged aquatic vegetation don’t obstruct their readings. But the winter comes with its own challenges, as the crew works through cold temperatures and schedules around ice and wind.

The side-scan sonar with interferometric swath bathymetry system—which, through some creative engineering, remains directly beneath the front of the boat—collects surface layer and depth data over a 150-meter-wide swath, while the sub-bottom profiler provides more detail on the sediment beneath the surface layer. The torpedo-shaped magnetometer detects the presence of metal material, which tells scientists if there are any possible shipwrecks or archeological artifacts in an area.

To confirm the data collected, the team also pulls up samples using a Petite Ponar grab sampler, which scoops patches of sediment so they can make sure their findings match what’s actually on the bottom. They take notes on the mud, sand, and shell they find, before pouring it back into the water.

Real-time bathymetric, or depth, data displays as a red bar on the lower screen, while the “loudness” or hardness of the bottom appears as red dots against a yellow background. An upper monitor shows the course of the research boat in the Patuxent. Photo by Joe Zimmermann/DNR

For ground truthing, or confirming their readings with material observations, the team pulls up samples and analyze the quality of the bottom, whether it’s mud or soft sand—or filled with oyster shells. The team sometimes also uses an underwater camera to look at areas of the bottom. Photo by Joe Zimmermann/DNR

Together, this information shows where there could be habitat for fish spawning, benthic communities, bay grasses, and—critically—oysters. The current Bay bottom mapping work is funded by a law passed by the Maryland General Assembly in 2022, supporting the department’s efforts to survey the extent of existing oyster reefs and potential future habitat. To grow to maturity, juvenile oysters require a substrate of hard bottom or other shells.

“Knowing the bottom type is crucial for implementing successful oyster projects,” said Chris Judy, shellfish division director of the Maryland Department of Natural Resources. “These surveys will update habitat maps that date back many decades.”

Surveyors first mapped Maryland’s oyster bars in the “Yates survey” of 1906 to 1911. Living on a two-decker house boat for the duration of the project, the hydrographic team relied on local knowledge to arrive at oyster bars. According to a 1997 DNR report, the Yates survey team would “run a zigzag or parallel series of lines across the bar to ascertain its exact limits,” with a local assistant holding a “chain-wire apparatus” and feeling the vibrations to determine condition or density of the bottom.

In 1975, the Maryland General Assembly funded initial work on a large-scale Bay bottom mapping survey. For much of this work, DNR crews dragged microphones across the bottom, recorded the sound, and later listened to the tapes to characterize the type of bottom. While the technology has changed considerably, the row-by-row approach, across one patch of the Bay at a time, has remained over the decades. That survey work resulted in the updated numbered oyster bars in charts released from 1981 to 1985.

Survey teams have continued intermittent work since then, but the current Bay bottom mapping work is the start of a comprehensive update to the 1980s charts, with an annual budget of $2 million from 2024 to 2026. During this statewide remapping effort, MGS surveyors or contractors also assist to assess the Bay bottom at DNR’s large-scale oyster projects before oyster plantings or other restoration work occurs.

Accurate bottom data allows scientists to focus their restoration efforts on the hard bottom that oysters can successfully repopulate. In Maryland’s large-scale restoration sanctuaries, scientists have seen promising signs for recovering local oyster populations, with considerable reproduction and the establishment of dense, vertical oyster reef structure.

The earliest Chesapeake surveys used the vibrations of chains to identify what laid at the bottom of the water. Now, the team uses high-tech equipment, such as the sub-bottom profiler, which beams real-time data back to the boat. Photo by Joe Zimmermann

But some of the process of the survey has remained largely unchanged over time, with crews carefully crossing sections of the Bay, back and forth, one at a time. Photo by Joe Zimmermann/DNR

The Bay bottom mapping team recently completed comprehensive mapping work at Eastern Bay.

As the Department of Natural Resources looks toward the new strategy for Bay restoration that focuses on shallow-water areas, Van Ryswick said bottom surveys could help to identify restoration opportunities in rivers and shallow waterways, areas that are a primary concern of the Whole Watershed Act. In addition to a larger boat that surveys more open water, the MGS team also operates a smaller vessel for shallow areas.

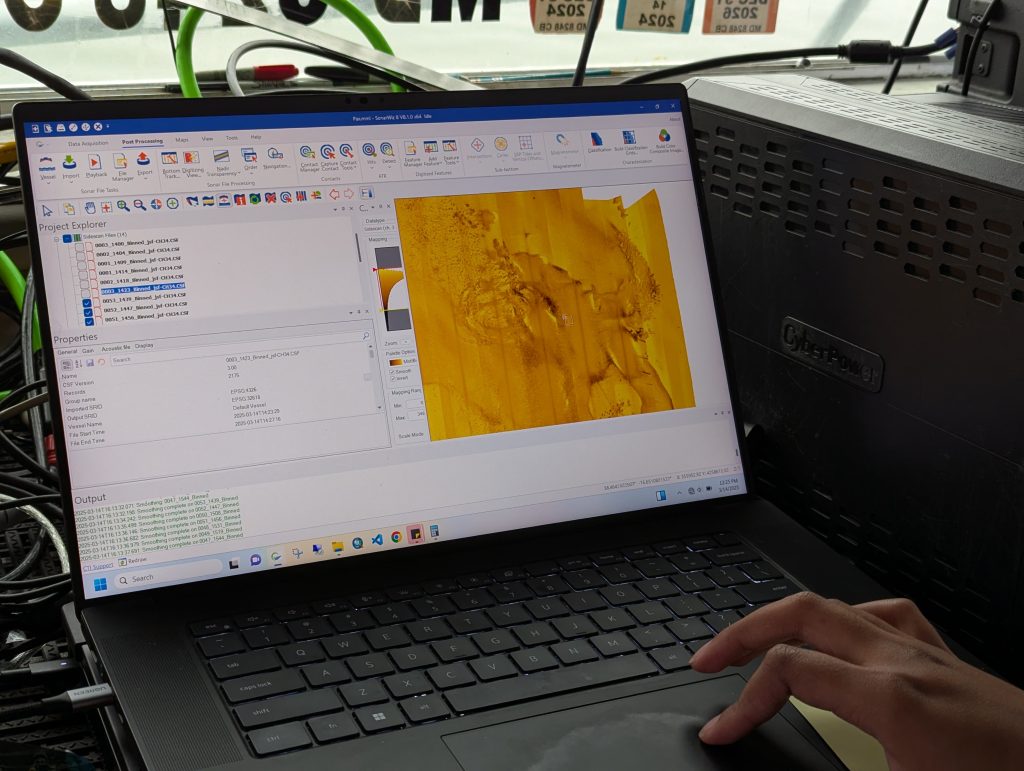

By the end of the day at the Upper Patuxent Sanctuary, the team had completed seven lines, putting about 368 more acres on the map. Branam started to process more of the data on the boat as they headed back to the dock, the area they had mapped filling the screen, line by line, in varying hues of yellow and red. What starts as a process of mowing the lawn ends up producing a vivid map of striking color, a catalogue of information that will shape the understanding of what lies beneath the water for years to come.

“The finished mosaic is really pretty,” Branam said. “It’s basically science art.”

On the way back to dock, the data from the day is compiled into one map that fills in line by line, showing a detailed image of the Bay bottom in bright reds and yellows, corresponding to different levels of hardness. Photo by Joe Zimmermann/DNR

By Joe Zimmermann, science writer with the Maryland Department of Natural Resources